Orozco the Embalmerseeders: 5

leechers: 3

Orozco the Embalmer (Size: 1.53 GB)

Description

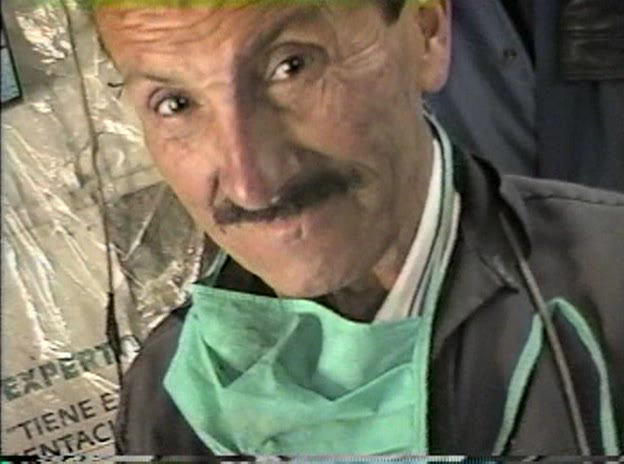

Tsurisaki Kiyotaka - Orozco el Embalsamador aka Orozco the Embalmer [+extras] (2001)

Warning: Graphic screenshots! http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0982908 Language Spanish Subtitles English & German sub/idx  CAUTION This is a very brutal and graphic documentary. I strongly suggest everyone to take a peek at the trailer first to see if their stomach is up to it : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-eABS_fR1y4&feature=related In any case, don't take it if you can't stand the sight of bowels, intestines and eyes gouged out. Intensely explicit, Tsurisaki Kiyotaka’s work is REALLY not for the squeamish. But while there is an voyeuristic element of shock and gore value, Orozco, el embalsamador is far from being a tasteless shockumentary. It is also strangely compelling. PLOT SUMMARY : Bogota, Colombia. Orozco is the oldest embalmer for the "Institute for Legal Medicine" where he has been working for more than 40 years. He survived the so called "La Violencia" - the age of internal disturbances in the 50's. He embalms five to ten bodies a day. He has embalmed over 50 000 bodies in his lifetime. NOTICE : Attracted to Colombia, the land of love and violence, corpse photographer Tsurisaki Kiyotaka is led to the most dangerous area called 'El Cartucho' in Bogota where public order is the worst in the world. There he met an old veteran embalmer, Froilan Orozco, in the neighborhood of "rue morgue". It was not surprising that Tsurisaki became interested in the profession and deeply impressed by the fact that as an embalmer Orozco could continue mourning for countless victims of violence and bloody history in Colombia. Is it social or bizarre? Is it beauty or bad taste? It's all up to you to judge what it is.   COMMENT The Japanese reporter-director Tsurisaki Kiyotaka left for Bogotá to shoot a report about Orozco in 1996. It was supposed to be a one-day report. Kiyotaka stayed longer, and came back much later than expected. This is how this astounding feature came to exist. The pictures are crude and rude. This is no horror film fueled by fake, cornstarch concocted, fantasy forged blood. This is a real documentarian's work that guarantees to take hold and twist your guts. However, this effect on your constitution was not, in any way, the goal of the director. Kiyotaka wanted a new kind of documentary due to the belief that the gross majority of films made in this school of filmmaking all looked the same. He wanted to bring something new to the form, as well as articulate a more profound statement about death. His film shows us, literally, a side of our lives – the after-death – which we do not know and ignore to maintain a sense of blind eyed bliss. He did not add any comments to the pictures. Only a shy, evocative score accompanies the observer, sometimes hardening the pain. The montage is basic; the film is assembled, rather, as a series of pictures. But the sequences are not abandoned at the fastidious moment when a horrible nude rotting body is about to be cut open. I have never seen images of dismantled bodies, from the inside and the outside, as complete as this. Not even on the science programs beamed through the television for the edification of those insomniacs held prisoner by the night. This documentary makes a significant offering to the amalgamation of true, scientific value. Through those images, we note that death is not only the last breath breathed. The body does not disappear instantly. Religion or culture facilitates the process of saying a definitive farewell to the departed by displaying the dead under its nicest appearance for a few lingering days. But this method of conjuring reconciliation for the bereaved requires the body to be cleaned and made beautiful. A process that is executed in a much less spiritual context. Thus, we see bodies changing from the state of a person kissed by mortality, to a corpse being carted around like a dead pig, to a cadaver that is cut up, stuffed with old newspapers and sewn back together with kitchen string. And then and only then, after make up and clothing, the body reclaims its human face. It takes the final appearance of the cherished one, resting peacefully on its last bed. The film makes no big deal about the details. A face is shown turned inside out in order to clean the underlying skull from its blood and cartilage. A knife plays peek-a-boo with the eye sockets to detach the face from the skull in a manner that is nothing short of staggering and painful. If the sequence had not have been filmed in one shot, you wouldn't believe that the pretty woman lying in the coffin before you was that mangled knot of elastic skin and hard bones. The film also reminds us that this is the minutia for many people in our society; not only embalmers, but also surgeons or those working in the ER. This realm of death goes on in the shadows of our ambitions without ever really forcing us to bare witness to it despite the absolute necessity it fulfills for our machine. A necessity that we don't really won't to be mindful of much less ever want to see. There is another aspect of this film, less choking at first glance, but wrongly so: the life conditions in Bogotá. It is a quality of life that finds sentence in the conduct of the medical police who arrive at a crime scene where a young woman has been shot. They remove her personal belongings, as well as her clothes; and start performing the first basic steps of an autopsy in front of an amassed crowd on a busy street intermingled with young children on their bicycles. Interestingly enough, the good people of Bogota are about as disturbed by this event as us Europeans would be disturbed by seeing someone faint in the street. Additionally, the hygiene, or rather its absence, leaves its mark on you too. Particularly in regards to the embalmers often working bare-handed on the dead. Once again, this film has a scientific or historic value. It is a documentary made from the inside. Kiyotaka has this ability to infiltrate the milieus he is studying. In regards to this work, Kiyotaka explains that it was very difficult to shoot the images of this film because of the very nature of Orozco’s job, but mainly because of the country’s work and life conditions. Being tossed into such a difficult world, as a foreigner, and being accepted was no easy job. But, says the director, it was even more difficult (not on the same level though) to sell the film and the two picture books, and to find galleries or festivals that would exhibit his work. Warning: screenshots depict gore   A FEW WORDS BY TSURISAKI KIYOTAGA It was in September in 1995 when I met Froilan Orozco for the first time. I was introduced to Orozco by Colombian photographer specialized in the dead Alvaro Fernandez Bonilla as he recommended me take photos of embalming. First I recieved intense impression on Orozco's smoldery features rather than embalming, and also I got attracted to his nihilistic darkness, speech and behavior that was short and to the point with confidence in himself. If it is the corpse as it stays still, I would take still photos. I thought Orozco was worth being filmed and I also wanted to make a film focused on him. In 1996 'V&R PLANNING' the AV manufacturer ever released 'junk' and 'death file' offered me to make some photoshooting for the new 'death file'. And the first thing I did was to take photos of Orozco and paid him five hundred dollars for that photoshoot. At that point both Orozco and I thought would work together for only once. Eventually the new 'death file' did not happen. The purge of cruel expression in Japan was progressing steadily. I never expected to see such an end of the century. However, I kept the coverage on Orozco without thinking of that situation I mentioned above. And every time I met him, unconsciously I was taking a video of him. Orozco did not claimed any additional fee against me. He was brusque and stoic like a martyr. What on earth was he thinking of me that came all the way from Japan just to film corpses? Because we didn't have much conversation and for Orozco he might think that I was not disturbing him, I was left alone. I also liked the situation with comfortable distance. The relationship between us was some what strange. Sometimes I wondered for how long our relationship would last, but I never expected it would end suddenly until the death of Orozco himself in February in 1998. The existence of him had such unparalleled influence in me. He died of hernia. That means the weight of 50 thousand bodies he embalmed crushed on him. It was the vocational disease. Though it might sound cruel, it was the death in harness with honor. Since the coverage was unconscious and sensuous one, when I think back of it now I have many regrets. Was the coverage like putting him into a corner might necessary? I was just there for him and I thought it might be important. Once I asked him such a thing, "For example, is it possible to take a video of necrophilia?", "1,500,000 pesos (1,500 dollars) including guarantee for the actor." That was way actual figure. "Just for reference, how about the snuff film?" Orozco put a grin and said, "huh, you got money ? It costs a lot." Was he teasing me? The story that Orozco once had smuggled cocaine stuffed inside a corpse into America got reality and sounded true to me. Actually during the heyday of drug war, the incidents where cocaine was found in the corpse occurred frequently. The method of Stuffing cocaine into the corpse of a baby and a woman acting like mother carried it out was popular in smuggling. Orozco also confessed such story when the camera was not running. Whether he might be a inhabitant in the urban legend or not, I don't have much interest in the truth of things. What I aim for is not a rough documentary, but a beautiful epic. - source: http://www.orozcoelembalsamador.com/public_html/en/contents_p_notes.html Warning: more gore   ABOUT TSURISAKI KIYOTAKA As a photographer in a crowded industry, finding your own niche might be a difficult task. For artist Tsurisaki Kiyotaka, a request to shoot a dead body for an S&M magazine has turned into a prolific career that has seen him photographing more than 1,000 corpses in some of the world’s most volatile areas. Tsurisaki has published six books, two of which, Revelations (a 12-year anthology of his corpse shots) and Requiem De La Rue Morgue have been released in France. He also directed a film, Orozco El Embalsamador, which looks at the life of a Colombian embalmer. Intensely explicit, his work is not for the squeamish. But while there is an voyeuristic element of shock and gore value, the photos are strangely compelling – portrait-like, still life, or journalistic reportage, each corpse bearing testimony to a tragedy. Originally an S&M porn director – Tsurisaki says his films were “set in the Pacific war, where the Japanese Gestapo torture Japanese high-school-girl spies” – he started shooting corpses in 1994 when the director of the S&M video company had the idea of setting up a magazine with a feature that included shots of dead people. “Before that, I had no experience as a working photographer, and apparently he asked a number of people if they would shoot a dead body, but no-one agreed,” Tsurisaki tells Bizarre. “At the time, I was newly unemployed, so I thought it would be OK to go overseas and shoot a dead body – why not? So I went to Thailand, was able to get the shots, it was fun, so I continued.” Did he ever. Tsurisaki has shot in places such as Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, and Russia, and the deceased are victims of murder, suicide, car crashes and the like. His pictures are taken with graphic candour, and he holds back nothing in terms of intimacy and the sensation of being there. Many of the horrendously mutilated bodies are obviously photographed straight after the death – which poses the question, how did he get access to these scenes? “In Thailand, the journalists from the local crime magazines would listen to the radio signals of the rescue teams and the police. So in the beginning I hung out with those journalists. Eventually, I got a lift from the rescue teams to the scene. It’s a country that has a culture of photographing dead people, in a way. They have a different, non-Westernised perspective on death.” However, each country comes with its own difficulties, and Tsurisaki would gamble based on intuition. In many instances, he didn’t even know how he would go about getting the shots until he got there. “Colombia and Mexico have these cultures where you can see many corpses in the papers, so given that background, taking these photos is OK. For Russia, there was a TV programme that would show crimescenes, and I followed their crew. That was in 1996, but that programme finished and I don’t think it’s possible to take these kinds of photographs any more.” Tsurisaki’s career has seen him held at gunpoint, nearly kidnapped by militant guerrillas, and caught in the crossfire in Palestine, but the country with the most impact for him was Colombia, where he shot his film Orozco in 1999. “It’s my favourite place in the world, being one of the most unstable,” he says. And he has a thousand other stories. “There was a Japanese S&M film producer who wanted to make a snuff film. I offered to ask around about it, and got told you can make one for a million yen (about £4,300). It’s cheap, but eventually they couldn’t get the funds together. And then, even if they did it, I mean, they can’t publicly announce it!” Tsurisaki considers himself a shockumentary- and Italian-film-loving “relatively normal” guy, and feels no overt psychological repercussions from the nature of his work. So what are the difficulties of the job? “The scene is never like how you want it, it never goes to plan, and it’s not like you can just pick up a dead body and move it. But then you can say it’s a limiting situation, so it’s interesting. Also, there aren’t that many places globally that will allow me to take photos of this nature.” He is called upon by the Japanese media as an authority on the effect of hardcore photos on people’s psyches after murders or incidents like the Aum Shinrikyo cult’s gas attack on the Tokyo subway in 1995. However, he says he’s had little resistance to his work, and, seeing as he is able to even exist as an artist, you could say Japan is relatively forgiving of his career. Moreover, he has a bevy of young, female fans, and there are various speciality museums that display his art. But conversely, Tsurisaki tells us this isn’t quite how he wants people to react. “Sometimes I feel bitter that I haven’t influenced society in a major way – like, say you go to someone’s house and they are growing pot. They will almost always have a copy of Burst High [Japan’s marijuana magazine]. “If someone commits a really deranged murder, I mean they should have my photos, right? No. In reality, the people who do commit murders, they have bad taste. You hear of them getting influenced by these cheap, crappy, sadistic films, but they haven’t heard of me. They simply have bad taste.” --------my rip------- Thank you to gungi for the previous rip and excellent announce that I stole! ---------my rip--------- ~~~~~~ Orozco el Embalsamador.avi ~~~~~~ File Size (in bytes):...........................1,408,292,864 --- Video Information --- Video Codec Name:...............................XviD ISO MPEG-4 Duration (hh:mm:ss):............................1:32:06 Frame Count:....................................132480 Frame Width (pixels):...........................624 Frame Height (pixels):.......................... Sharing Widget |

All Comments